Why BiblioCommons?

Why BiblioCommons?

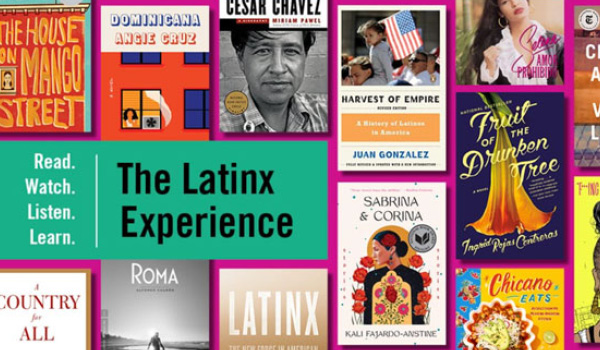

Success Stories

Hear how Library Partners are making an impact in their communities

Our Story

A better online catalog was just the beginning

Libraries We Work With

Take a look at all the Partner Libraries that subscribe to BiblioCommons

News

Stay up-to-date on the latest company updates with news articles, press releases, and announcements

Solutions

.svg)

Solutions

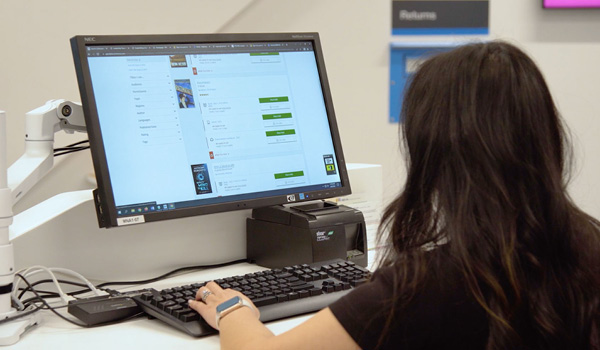

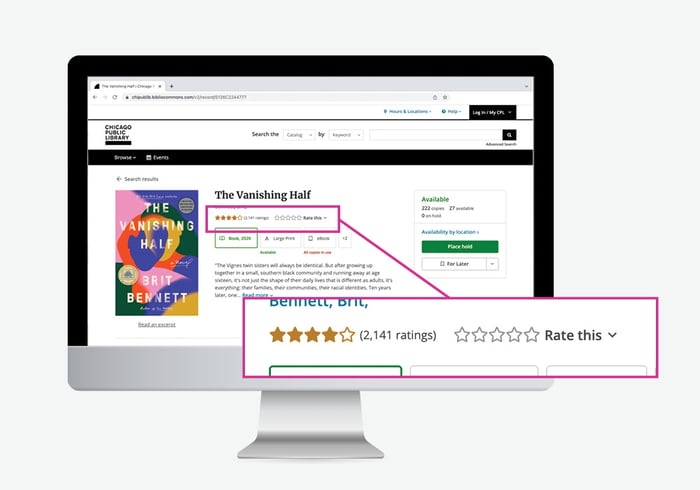

Discovery Layer

Accurate search results, easier borrowing, and endless discovery pathways

.svg)

Discovery Layer Add-Ons

Unlock more ways to engage with patrons

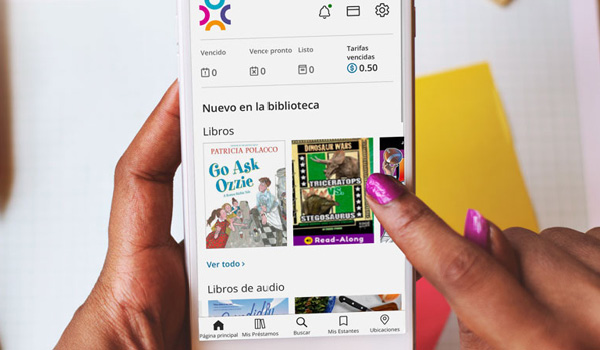

Mobile App

Deliver engaging content and promote discovery wherever your patrons are

Website Builder

Showcase the best your library has to offer with a fully integrated CMS and webpage builder

Events Calendar

A patron-friendly way to manage and promote your library's programs and events

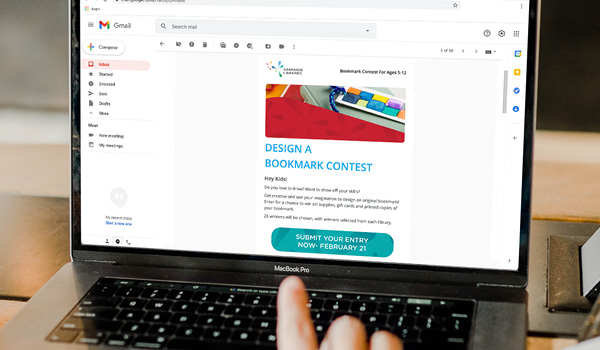

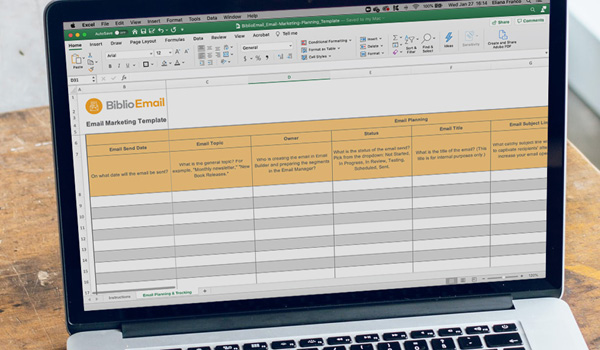

Email Marketing

Email Marketing That’s Personalized, Automated, and Integrated

Resources

Resources

All Resources

Access all types of resources like guides, templates, videos, and reports to learn best practices and get new ideas

Webinars

Register to attend upcoming live webinars and get access to on-demand webinar recordings that cover a variety of topics

Blog

Dive into our blog to read about library trends, expert opinions, fresh ideas, and practical tips that you can use in your day-to-day

Newsletters

Sign up to receive the latest in public library topics, new product features, and upcoming events in your inbox

BiblioCon

Learn from public library staff and leaders that are experts in creating unforgettable, fresh, and engaging experiences